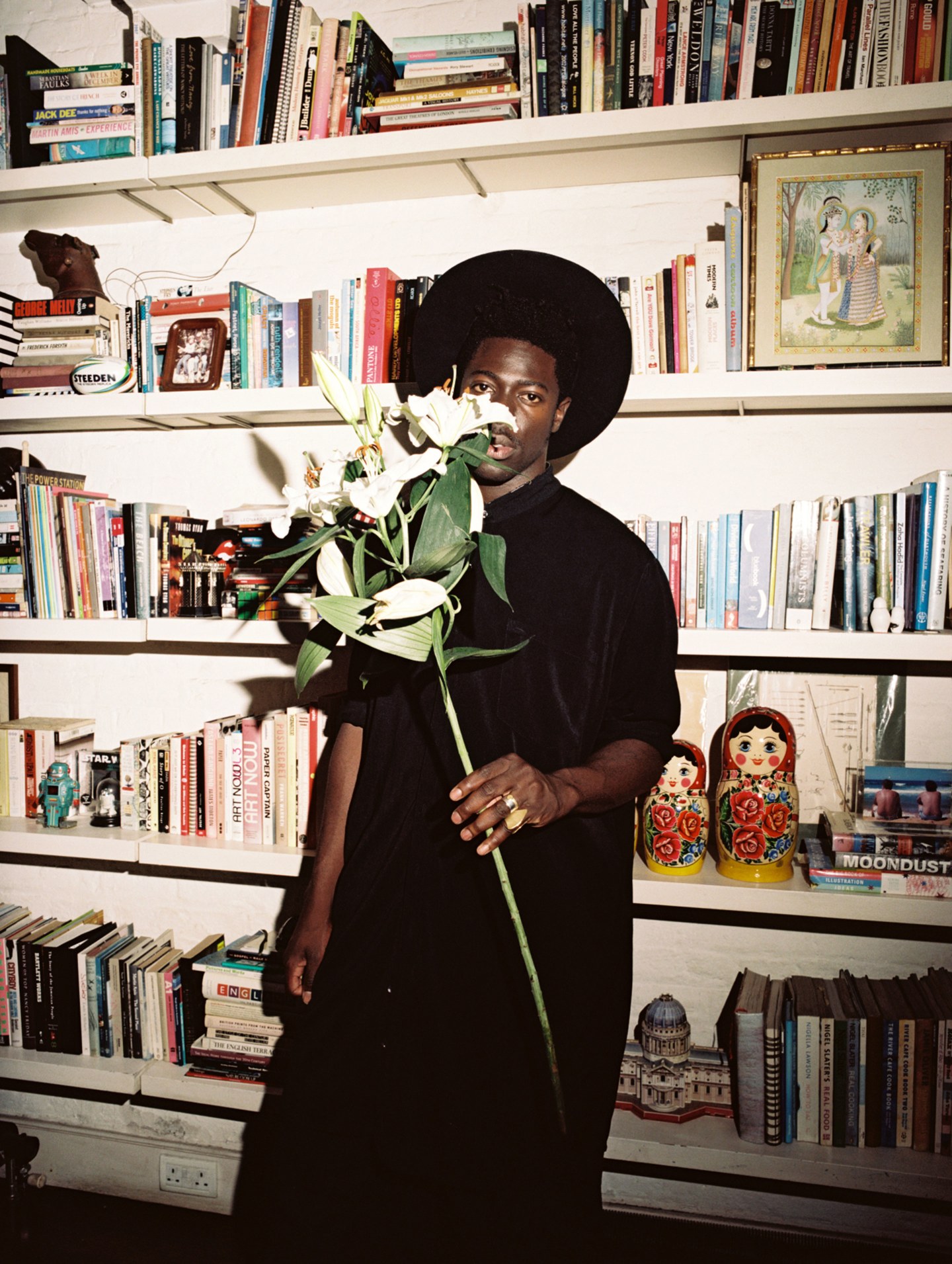

Moses Sumney has a sense of humor that disarms you. When we first meet, on a crisp August day, in the airy living room of the plush three-story east London apartment he’s staying in, I ask, “So this is a friend’s place?” He replies that’s it’s his, actually. There’s a serious tone to his L.A. accent, so it takes me a second to catch the sarcasm; he starts piling new lies on top of the initial one. He bought it 10 years ago, he says. He built it from the ground up, with his own two hands. The 26-year-old singer-songwriter’s playful facetiousness and big laughter is only a surprise in contrast to his music, where he’s deeply sincere and often vulnerable.

Moses’s lo-fi debut EP Mid-City Island in 2014 first laid his songwriting bare to the world. Made alone on his bedroom floor on a four-track recorder gifted to him by Dave Sitek of TV on the Radio, it had an unvarnished feel. With a follow-up single released by Chris Taylor’s label Terrible Records, and last year’s more polished and stylized EP Lamentations, he gradually built a reputation for piercing electronic soul songs. Along the way, he’s quietly developed a fanbase among other brutally emotive songwriters: he’s appeared on Solange Knowles’s “Mad,” (and, as a member of her oft-referenced group chat, frequently pops up on her Instagram), and toured supporting James Blake and Sufjan Stevens.

But his debut album Aromanticism (out September 22 on Jagjaguwar) is his most fully realized work yet. Created while traveling the world over the course of three years, the record features Sumney’s own production for the first time, as well as his improvisations on bass, synth, and a guitar solo inspired by St Vincent's shredding. The record also includes contributions from Thundercat, Paris Strother of R&B group KING, and Matt Otto of Majical Cloudz. The concept for the project sprang from a late-night googling session, when Moses discovered the not-yet-dictionary-official term “aromanticism”: the inability to experience romantic love. “I’ve had a lot of romantic interactions,” he reflects. “I was present to some degree, but I wasn’t in love; I wasn’t able to reciprocate. I was like, Do I need to go to a doctor, or write an album?”

The musical canon is full of songs about loneliness, but Aromanticism is something different. Moses both celebrates lovelessness, and quivers at the thought of it. On the reverent “Doomed,” he poses deeply anxious questions: “Am I vital, if my heart is idle? Am I doomed?” Elsewhere, he’s flirtatious, as on the shimmering, flute-enriched “Make Out In My Car”, and vulnerable, as on the starkly intimate acoustic ballad “Indulge Me.” Over a lunch of ceviche in east London, Moses explains that solitariness is both a comfort and a challenge.

Do you remember the moment you discovered the term “aromanticism”?

Yeah, I was in my apartment in 2014. I found the word online, and was like, Wait, this sounds like exactly what I’ve been thinking and feeling. Trust me, I’m hyper-aware of the way that this seems like WebMD culture. A few years ago, when I was 20, I felt like I had ADHD, but I didn’t know what that was called, and I started googling symptoms obsessively. I spent weeks researching it, and fully felt comfortable diagnosing myself. It was such a strong sense of relief — and then later I ended up going to see a psychiatrist and I actually got diagnosed with ADHD. With this whole aromanticism thing, I had that exact same feeling of relief. I had the same feeling of like, Okay, this is a thing that is precedented, there is a name for this.

By writing about it, did you want to subvert the romantic tropes of pop music?

I’m not sure. I’m talking about loneliness, but when people want to be subversive, particularly in pop music, the thing to do is go anthemic. Mid-2000s, there was a lot of “I can do it all by myself, I don’t need nobody else” attitude. That felt dishonest [for] me. Conversely there’s a lot of music about being alone, you know: “Lonely, I’m so lonely” [to the tune of Bobby Vinton’s 1962 classic “Mr Lonely”]. I wanted to have these songs about isolation and sadness, which there’s tons of in the world, but be able to put them in context, to point in a specific direction towards something that’s never talked about. People don’t think [aromanticism] exists. As a concept, it’s probably a bit scary for people.

In the book Against Love, author Laura Kipnis breaks down how our society’s obsession with romantic love is unhealthy. Do you think the romantic ideal can be bad for mental health?

When you’re conditioned to look at something as normal, the sadness that can come from not being able to obtain that is super taxing on your mental health. But also, you can be in situations that are psychologically fucking you up, but there’s a commitment to stay with that, because that’s what you’re “meant to do.” You get absent fathers, or moms with post-partum depression. It’s complex, because humans are social creatures, and I actually do think we need other people in order to feel sane. It’s really unhealthy, the idea that you need another half to make you whole, but also I don’t think it’s particularly healthy to totally self-isolate. There needs to be a balance, and I don’t think there is, currently.

"I think that romance is very obviously a political tool, and a capitalist device.”

On a bus from east London to the south bank of the river Thames, Moses is stoked to find the top deck is entirely empty. He takes a selfie, sunglasses on, with the empty seats stretching out behind him. He does a lot of his lyric writing on the bus, he tells me — a habit that began when he was a child living in Accra, Ghana, catching public buses for two or three hours across the city to get to school. He composed most of Aromanticism’s lyrics while staying in remote, Wi-Fi-less cabins in the mountains of North Carolina and California.

Moses was born in San Bernardino, a city an hour east of L.A.; at the age of 10, his parents, both pastors, moved the family back to their home country of Ghana for six years. It was a time that was tinged with homesickness for him, defined by the CDs his dad would bring back from the U.S. Moses taught himself to sing by carefully copying the runs and adlibs of Beyoncé, Justin Timberlake, and Usher. He wrote his own songs from the age of 12, but kept it a secret, hiding his songbook under his mattress. “None of my friends knew that I wanted to sing,” says Moses. “I was a loner; I’d ride my bike around with some other guys from the neighborhood sometimes, but I didn’t have a lot of school friends. But [Ghana] taught me how to spend time alone, which is something everybody needs to learn.”

After returning to the U.S. at 16, he went on to study creative writing at UCLA. At 20, he finally began sharing his privately honed folk music with audiences. He competed in a dorm room talent contest, joined an indie rock band, and eventually graduated to open mics in coffee shops off-campus. Via a college radio show he hosted, he struck up a friendship with KING, who invited him to open for them at an artist residency at the Bootleg Theater in 2013. After a few weeks of playing support for them, the room began filling with A&Rs and booking agents who came to see him. Word eventually spread to Dave Sitek, and later Solange, who invited him to play a Saint Heron showcase for New York Fashion Week in 2014. There, Moses met both the artist herself and Chris Taylor. While Moses’s craft comes from an isolated place, it’s also blossomed with the encouragement and support of others — a blessing he doesn’t take for granted.

What was it like working on A Seat at the Table?

It was really fun, and it felt kind of spontaneous — Solange just texted me. This was actually before we were really close; she just asked if I’d come in and sing on something. She played me a bunch of songs from the record, and I was just like, Holy shit. I knew when I heard the record that it was earth-shifting. I had never really heard music like that. It felt like such a realization of her vision. Because I do a lot of vocal layering stuff, she was interested in me doing that kind of layering-slash-choir stuff on the record. So on the song “Mad,” there’s a bunch of layers, and because I sing in falsetto, there’s moments where you can’t really tell the difference between her voice and mine.

Do you see parallels in the way that you both work as artists?

Yeah, totally. Meeting her has been really good confirmation for me, because there’s a lot of things where I’m like, Am I crazy? But she does the same shit! She really does control every aspect of what she does — she’s so involved in the visuals, the production, she writes all the songs herself, and that’s a big thing for me as well. I guess the thing I didn’t realize [before working with her] was that even though I’m not always the one literally sitting at the computer, all the ideas are coming from me. I’m directing them, and I’m guiding the sound when I’m working with an engineer.

There’s a way that male super-producers direct other producers, or direct engineers, and a lot of it is dictation. I’ve been in situations where this is happening, it’s like, “Press this, record this.” Seeing [Solange] and the way she dictates everything makes me realize I do literally the same thing when I’m in a session, and it really gave me a confidence to own that. First of all, women get this way more than men do, generally — the idea that they’re not the producers of their own music. But I think also when you’re a vocalist and that is your primary thing, and also when you’re a person of color, people are very quick to make you feel like your ideas belong to someone else. I got that a lot. So I felt a connection to what she does.

At the Tate Modern, Moses sings softly to himself as he walks around the gallery’s latest exhibition, Soul of a Nation: Art in the Age of Black Power. At times colorful and optimistic, at others grimly realist, the collection brings together various prominent works by black American artists during the height of the Civil Rights movement. One of Moses’s favorites is “America the Beautiful,” a 1960 painting by Norman Lewis, which depicts a Ku Klux Klan gathering as angular splatter of white on black.

But while the subtlety of that painting is profound, it’s also important that art exposes the raw brutality of oppression. That’s what drew Moses to the recent TV adaptation of Margaret Atwood’s The Handmaid’s Tale, which he describes, while walking around the Tate, as a must-watch full of “feminist violence.” It can feel good, he says, to see the real brutality of the world as marginalized people feel it, without softening the sharp edges. Another painting he admires — Faith Ringgold’s blood-spattered “American People Series #20: Die” — has a similar effect.

In the bookshop after the exhibition, Moses buys Audre Lorde’s Sister Outsider, which he’s already read, but wants to own a copy of. Her essay “The Transformation of Silence into Language and Action” was really important to him while writing Aromanticism, he explains, as was Maggie Nelson’s The Argonauts, a memoir about the writer’s marriage to her transgender partner, and their domestic life. As Moses puts it, “She’s not really trying to talk about government and laws, she’s just talking about her relationship — which operates under the government and its laws. [She writes about] the way that disrupting the actual body is a disruption of political oppression, whether it intends to be or not.”

Aromanticism is not a record of overt political statements, but it is similarly impossible to separate it from its creator’s identity and perspective. Nothing is apolitical; not even who we fall in love with, or don’t.

Is this album just about your personal experience, or do you also have a political argument against romance?

I think that romance is very obviously a political tool, and a capitalist device. I’ve even thought recently, it’s quite good for the economy: the amount people spend on weddings and gifts. Also, [romance] just can’t be separated from a patriarchal structure — like the idea that in a homosexual couple, one person is the masculine, and the other is the feminine. Ultimately we keep going back to those two figures on the wedding cake as the archetype, even for alternative relationships.

Is that the idea you’re exploring when you sing, “We cannot be lovers/ Because I am the other” on “Quarrel”?

When I wrote that song, I was thinking about interpersonal relationships and how they’re all impacted by systems. I’ve lost a lot of friends, because I’m very cut-and-dry about social issues. I just reached a personal point where I’m like, “If you can’t question the inherent oppressive nature of society, I don’t want you in my life.” I had a friend in college that I cut off because he would make Native American jokes and black jokes. I was like, “Don’t talk to me ever again.” Except we were roommates. I’m that kind of person. He said to me: “You complain about the oppression of society, but you walking past me in the living room and not responding when I say ‘hello’ to you is the same thing. You’ve oppressed me.” And that was really deep — because it’s stupid! But it was like, Wow, this is the way people with privilege think. It was interesting, the idea that he thought we were equals in our relationship.

To play devil’s advocate, what would you say to someone who asked: “Why write about aromanticism when the world needs more love right now”?

Saying the words “the world needs more love” — using those words as a political device to imply that love all round is going to produce equality — is ignorant and unrealistic. The problem with the world is not that people who are different don’t have enough “love” for each other. The problem is that the people with power insist on using it, and maintaining it for themselves. Ultimately, when people say “we need more love,” what they are telling oppressed people is that they need to love the person that’s killing them. And what do they have to gain from that? A clear conscience? Some promise that in the afterlife, after they’ve been murdered by the people taking resources from them, that they’ll go to heaven because they have warmth in their hearts? It [goes back to] what we were talking about earlier with “Quarrel” — someone can love you and still be oppressing you, still not listen to your voice. Emphasizing love is a waste of time. What we need to emphasize is the dissemination of power, and a deconstruction of hierarchical structures that keep people at the bottom, and keep others at the top.